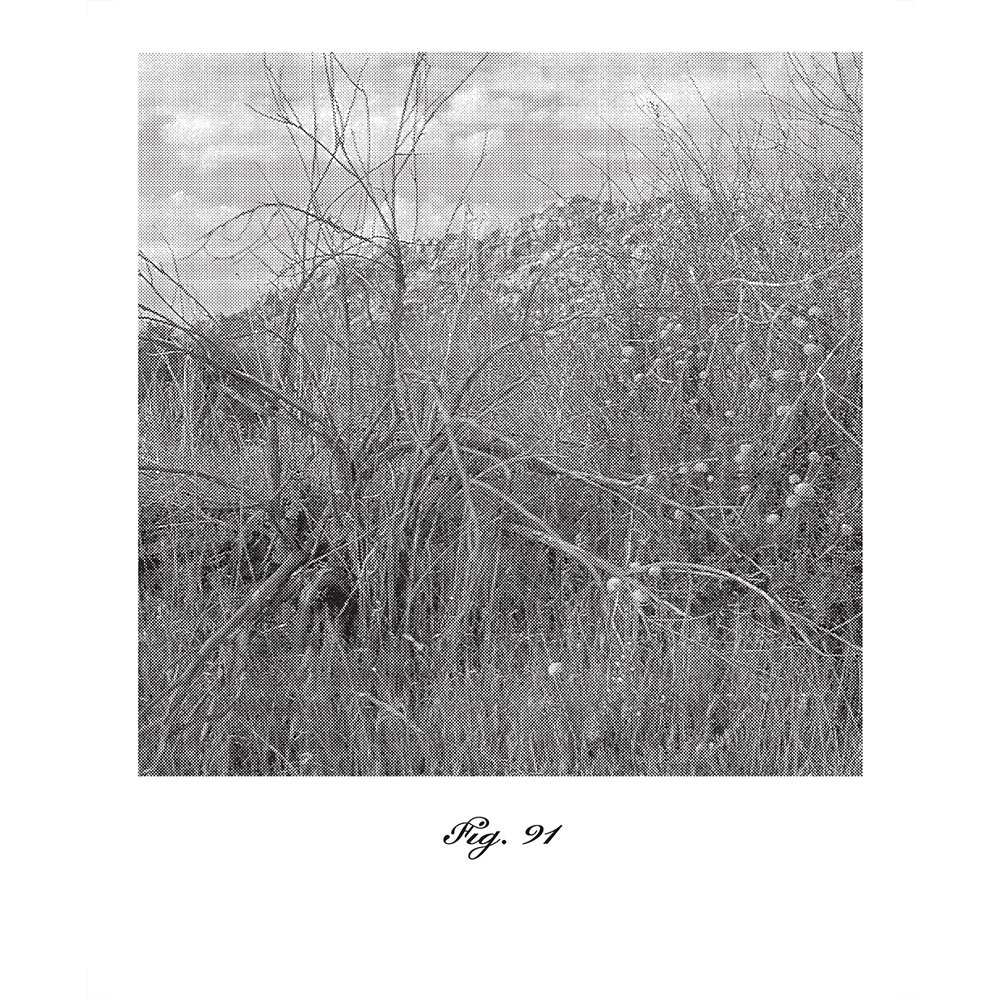

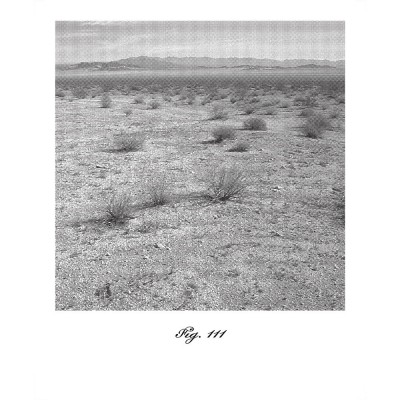

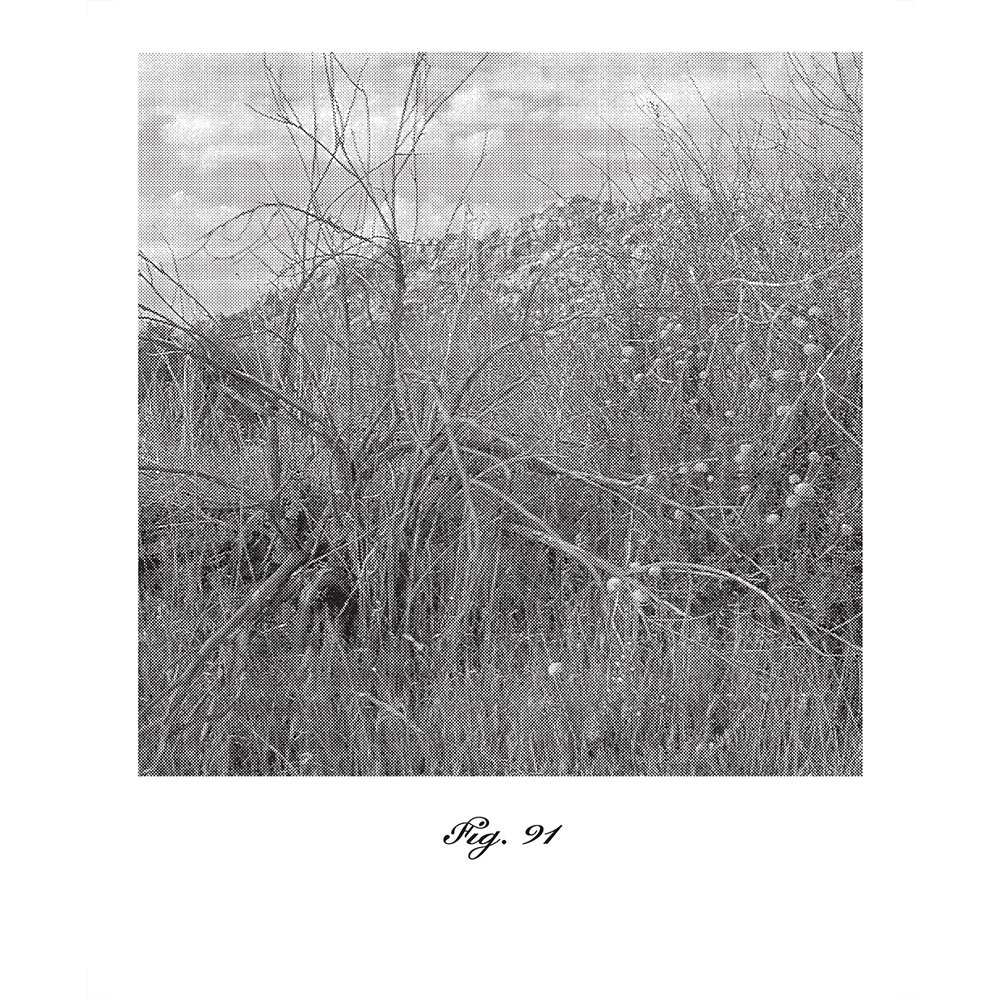

Fig. 91

Rudy Vanderlans

2006

58 x 46 inches

Carbon pigment print on canvas over stretcher bars

Edition of 10

INQUIRE

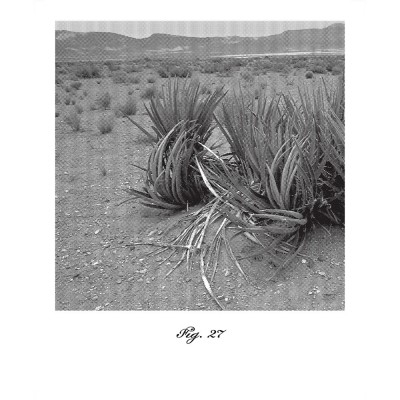

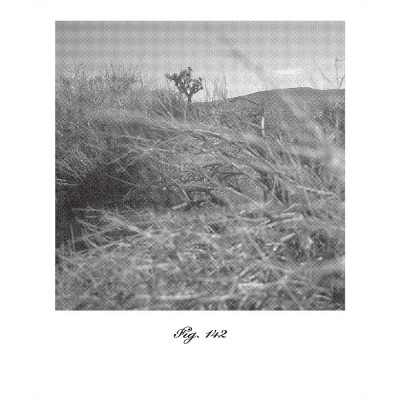

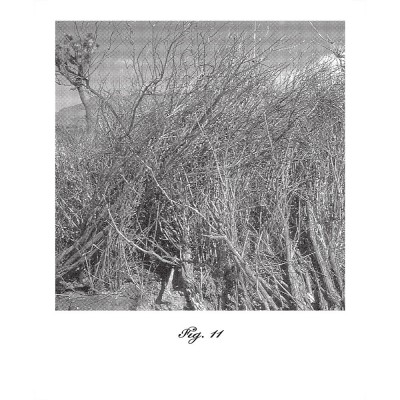

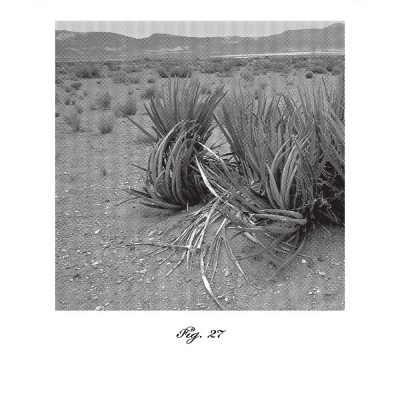

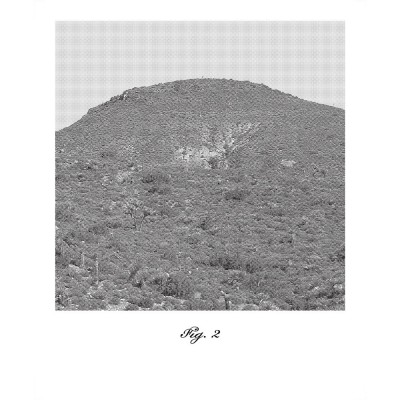

13 Big Pictures of Western Landscapes

by Rudy VanderLans

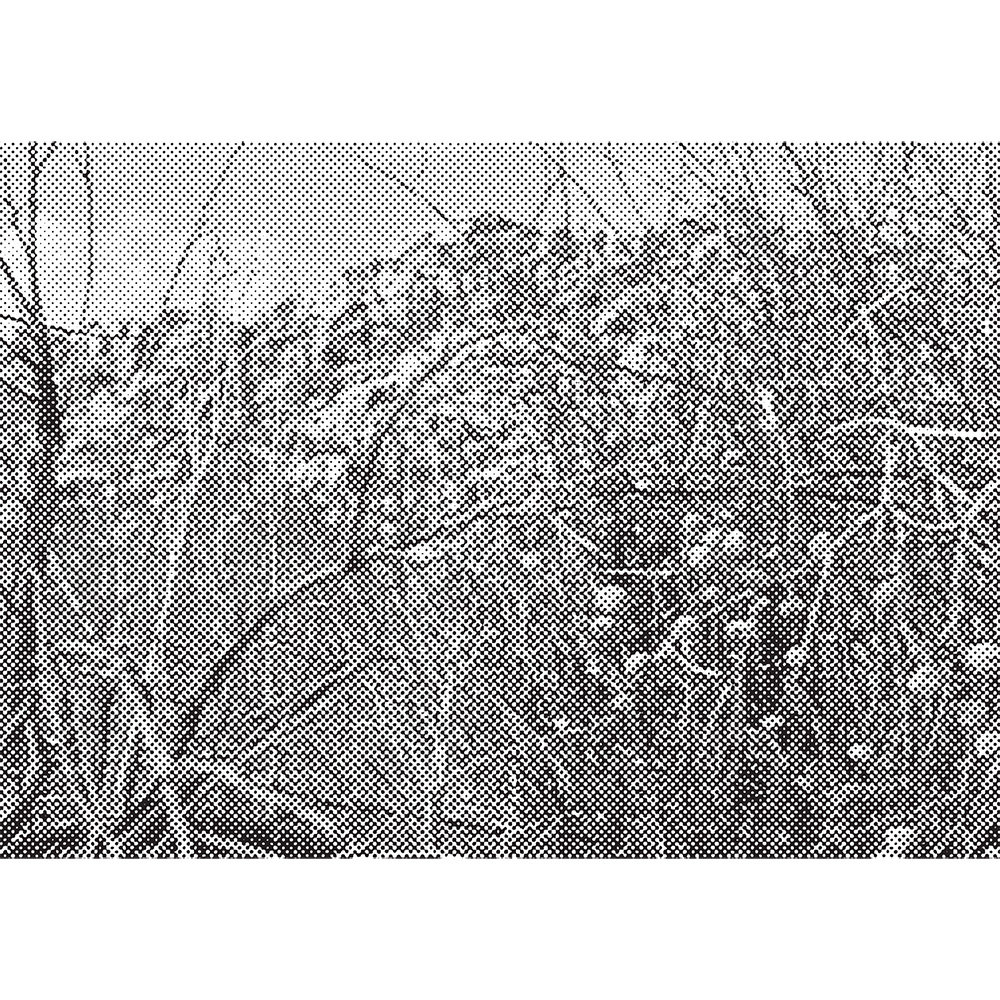

All art finds its common quality in the halftone dots used to reproduce it. That’s the one sentence I was able to cobble together that said something meaningful about the subject of these photographs. But isn’t the subject of these photographs the western landscape? you ask. Perhaps you’re right. But I’m not sure. Anyway, I felt the urge to write a clever story to distract from the fact that blown up halftone dots are a visual cliche—except of course in the hands of Roy Lichtenstein and John Baldessari, but that’s a different story.

What exactly are halftone dots? It’s a complicated technical issue but let’s just say that without the halftone dot it would be difficult to reproduce images in books and magazines. So you can see they play an important role, particularly in art. Actually, most people get their first glimpse of art in printed form—in art books, encyclopedias, catalogs, and magazines—which is to say they usually see art first through the medium of the halftone dot, which in the case of Roy Lichtenstein’s work should make you wonder where the original art ends and the reproduction starts. But again I stray.

So why use blown up halftone dots when they carry such baggage? Well, it’s a curious story that started when my friend P., who is a well respected San Francisco photo dealer, looked at one of my photo books and said: “I like these photos but the reproductions really suck,” or words to that effect. This struck me as an odd remark because it seemed that P. was assuming he was looking at reproductions of traditionally produced landscape photos. Such photos and their reproductions have a certain standard to live up to, especially in the mind of photo dealers such as P., and mine fell short by about a mile.

P’s initial reaction to my book of photos was no big surprise. In the world of art it is common practice to first produce originals, and then, when desired, reproduce the work in catalogs, books, invitations and other printed materials. Whenever a work of art is reproduced, the goal is always to match the original as close as possible, which is never easy, sometimes impossible, and always requires the expertise of skilled laborers such as graphic designers, color separators, scanners, and printers. Yet in the end, the reproduction is almost always inferior in quality to the original because the technique and materials to make the originals (various) are different from those used in the reproductions (halftone dots).

What P. was looking at in my book, however, were not reproductions of originals. And the reason they didn’t look like the costly reproductions that photo dealers usually drool over is because the book was designed to meet very specific production parameters: cheap uncoated paper, coarse halftone dots, a single color, etc. See, I was after a particular effect, let’s call it “cheap, third-world printing,” an effect usually avoided in fine art photography books, particularly the ones dealing with landscape photography. I wanted to make a comment about the near impossibility of perfect reproductions and at the same time make a book that had a unique quality all its own. The photos were processed not to match an “original” but to fit the context and concept of the book. They were scanned, cropped, and printed to look the way they do on purpose. In that sense the photos in the book are the originals.

P’s honest response to the book gave me an idea, though. I could turn the relationship of original and reproduction upside down by making large fine art prints based on the images in the book, like a bizarro world art publishing project. By using nearly the same reproduction method (by enlarging the halftone images from the book), I could arrive at a closer approximation between original and reproduction. I wasn’t sure what the deeper meaning of it was, but in the process I would raise all sorts of questions about representation, expectation, mediation, original, reproduction, and let’s not forget, visual cliches. Asking questions is often all you need to do in art, so I figured I was on the right track.

That’s how I arrived at these prints. Somewhere during the process I put together that sentence, “All art finds its common quality in the halftone dots used to reproduce it,” which sounded just terrific. It seemed like I was getting at the essence of something. Perhaps even a perfect justification for using a cliche. Then I was reminded of your question at the beginning of the story regarding the subject of these photographs and realized that if you can enjoy these images for what they are, 13 big pictures of western landscapes, that’s even better.