shop

News

new press for Alice Shaw's "Golden State"

August 21, 2015

We're pleased to see Alice Shaw's "Golden State" getting the praise it deserves! Below are a couple of articles that have featured the show recently:

http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/Alice-Shaw-finds-gold-in-California-culture-6451051.php

These days Alice Shaw’s old Mission neighborhood is awash with the signs of S.F.’s latest gold rush: tech buses, Teslas and carousing brogrammers.

So the subject of all that glitters feels like a natural one for the California-bred conceptual artist. At “Golden State” at Gallery 16, she spins further from photography, which she has taught at San Francisco Art Institute, and toward readymades, textiles and tweaked found objects.

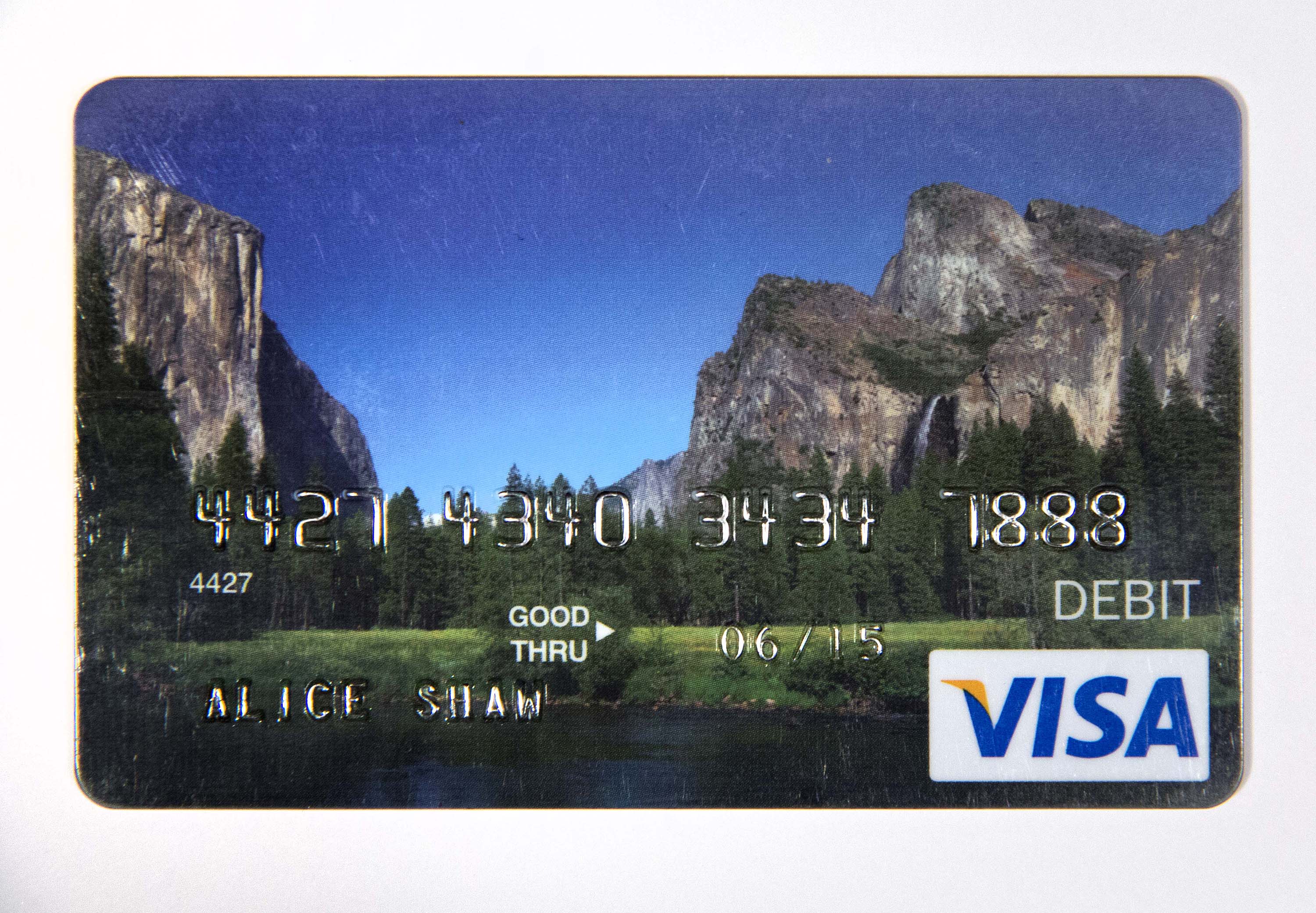

In her irreverent sight lines are drivers of California culture like commodities, celebrity, religion and that precious urban asset — parking. They play out in the form of an “Unemployment Debit Card for Out of Work Artist From the Ansel Adams School of Photography” and a gold-leaf-embellished “Jesus and His Disciples,” depicting uniformly begowned “icons” and an alt-Christ Jared Leto.

— Kimberly Chun

Continuing through September 4, 2015

Conceptual artist and photographer Alice Shaw deploys her abundant talent and wit to seamlessly blend humor and serious insight in this newest body of work, which comments on much of what the golden state of California is known for: the Gold Rush, fame and celebrity, enormous wealth (as well as economic disparity), even agriculture. For many of the works, Shaw alters found images, many of celebrities, and enhances them by coloring in the background or otherwise decorating them with gold or silver leaf. “Pot of Gold–fame (LA)” features a two-page fashion magazine spread with the headline “Red Carpet Rainbow.” Photos of female celebrities, each in a monochrome dress, are arranged such that, across the page, the colors form a rainbow. Shaw puts a gold halo over each woman’s head, a clear reference to saintly pre-Renaissance paintings. One can also draw out the association between rainbows and the proverbial pot of gold, which is also referenced in “Pot of Gold–Riches (SF).” This piece shows a hand-drawn rainbow dropping down to the lower right corner on a postcard picture of an actual rainbow arcing over the Golden Gate Bridge. Acidly reflecting on celebrity’s place in our culture, Shaw trots out people famous as much for their bad behavior as for anything legitimately earned. A sheet of (fabricated) stamps are appropriately called “Forever Stamps (Paris Hilton, Lance Armstrong, Lindsay Lohan, Barry Bonds, Britney Spears, Tiger Woods, Miley Cyrus, Charlie Sheen).” The title speaks for itself.

Touching on wholly different sector of wealth in the state, “Money Tree” features the elementary school cliché of an avocado seedling sprouting in a mason jar, the pit suspended above the water with toothpicks. The pit here is painted gold. Called to mind in an instant is the key role of agriculture in California’s economy and the ongoing drought. Taking a look at the less glamorous side of California living is “Chariot,” a picture of a beat-up gold sedan parked curbside in front of a Mexican restaurant, a taco truck parked behind it. Our Latino population provides a great deal of the cheap labor for many of the thankless, grueling jobs in the state, a key component behind California’s wealth. For many among these populations, life is a little less shiny.

Review of Alice Shaw's 'Golden State' in SFAQ

August 01, 2015

Congrats to Alice Shaw on a fantastic review by Leora Lutz published July 31 for SFAQ. Read the full piece below or visit the piece on SFAQ's site here.

ALICE SHAW’S GOLDEN STATE, WORTH ITS WEIGHT IN GOLD

BY LEORA LUTZ

JULY 31, 2015

Alice Shaw’s solo exhibition, Golden State at Gallery 16, takes its title from the nickname of California. Throughout the exhibition, there are references to the Bay Area in particular, featuring iconography such as the Golden Gate Bridge, but there are also references to Los Angeles and its fixation with fame. Further narratives include California’s car culture, religious diversity, shopping, and body image, but one glaring observation is the overarching theme of money and commodification. Several pieces in the exhibition are accented with gold leaf, which lend a regal quality to otherwise banal objects such as tourist postcards or pop culture imagery, such as Paris Hilton. Likewise, concepts of worship and worth are called into question. During the opening reception, when asked about the use of gold in her work, Shaw stated that she is commenting on increasing the value of the work by applying gold to it.

Alice Shaw. “Entitled #1 (Paris Hilton),” 2015.

Archival pigment print,

4″ x 3″

I would argue that the gesture also places the work within the context of monetary exchange. If an artwork has a subjective value, applying gold to it renders it a competitive object for trade on the market. In 2005, gold was worth on average $400 an ounce since the late 1970s, and prior to that it trailed at $35 an ounce since the late 1700s. Currently, the price of gold is slightly over $1,095 an ounce. Last fall, it reached $1,313, and in the summer of 2011 it spiked to $1,901, an all-time high. After spending some time on business journals, I learned that the value of gold is in direct correlation with the value of the US dollar. When elusive and speculative value decreases, people look to tangible goods such as gold or real estate to invest in, and therefore the demand increases for these goods. Basically, since the economic crash of 2008, gold has increased steadily in value. The dollar has slightly propelled itself back up again, but it is still worth only half of what it was in 2001, whereas gold has only steadily increased overall, now exceeding what the dollar was worth in 2001. Subsequently, as the value of the dollar increases, the price and ultimately the value of gold should go down (as will real estate). Art however, does not operate with this kind of exchange, but in general its value increases over time, and is oftentimes subject to trends in taste or publicity.

Alice Shaw. “Inflation,” 2014. Paper, engraving, and 22k gold leaf,

3.5″ x 6.25″

This brings up several arguable notions about the “art market” and the value of art beyond its role as a mere communicator of commodity. By communicator I mean that artists often use the economy as a subject for critical commentary in their work. The sad irony, as many of us know, is that art prices are often inflated by other notions of fame or popularity that are tied with the reputation of the artist. Unlike gold, an inert thing, people yield contentious and constantly fluctuating value that is subjective and wholly dependent on many other factors besides raw goods. So, the real argument with pricing art is not with the objects themselves, but with the value of the people who made the object or with the reputations of those who represent or exhibit the artists’ work. Not to open an entirely different can of worms of how gold is acquired and the value of people who mine it, let us return to Shaw’s exhibition and how her work is contending with arguments surrounding the potent value of subject, imagery and material.

Alice Shaw. “Jesus and His Disciples,” 2015.

Offset print and 22k gold leaf, 10.5″ x 32″

Jesus and His Disciples is an off-set print featuring a re-appropriated image from a pop culture magazine of red carpet starlets in their gowns, such as Jennifer Hudson, Scarlet Johansson, Keira Knightley, who are accompanied by Jared Leto (sporting a beard and long hair). The headline of the magazine reads “Red Carpet Risk Takers.” The text claims that, by wearing a daring outfit in public, one is taking a risk. The confusion here is that the risk is a materialistic one: a risk of ruining one’s livelihood or living without actually risking one’s life. The background behind everyone is embellished with 22K gold leaf, hand-applied by Shaw. The gold renders the subjects as icons—most akin to an illuminated manuscript—but the double entendre of icon is also situated in American culture’s fixation with celebrity worship. The worship of the almighty dollar is also suggested in the piece Inflation: a dollar bill with a 22k gold leaf halo surrounding George Washington’s head.

Alice Shaw. “Silver Dollar,” 2015. Digital Daguerreotype, 3.5″ x 6.25″

In addition to gold, Shaw also incorporates silver in some of the works, which brings up another conversation about the value of precious metals and their trade worth. For example, the counterpart to Inflation is the piece Silver Dollar, which is a daguerreotype of a one dollar bill. Ironically, this piece may be more valuable than the other simply because of the rarity of its material as a photographic process that is on its way to possible extinction. However, unlike gold’s current value at over $1000 per ounce, as mentioned earlier, silver is only valued at around $14.50. This comparison is particularly apparent in two small embellished postcard images that appear to be from the late 1950s. Golden Gate features an image of the Golden Gate Bridge with the sky above covered in 22k gold. In contrast, the Bay Bridge piece titled Silver Gate features the sky covered in silver leaf over the still existing western portion of the bridge spanning from Treasure Island to San Francisco; the silver usage implies that the East Bay is the lesser valued location. Incidentally, the eastern half of the bridge is being deconstructed at this very moment, fading into extinction like the daguerreotype, although much faster.

Alice Shaw. “Key To The City – San Francisco,” 2014. Brass, 1″ x 2.5″

Shaw is predominantly a photographer, and the use of appropriated imagery in her work is further commentary of the value of the images. Photographs convey meaning with the subjects they represent, which is where the true value lies, not in the cost of the paper to print to image upon or the amount of time it takes to snap a photo. Yet, through embellishing her work, Shaw renders the photos as hand-made objects, thereby challenging their singularity as a two-dimensional documentation, and recognizing photography as something more. This tactile quality extends to several three-dimensional pieces in the show as well, from altered credit cards to a one dollar bill, folded into the Coit Tower, and a real key carved with the San Francisco skyline.

Alice Shaw. “Comforter,” 2014/15.

Satin, polyester, and thread, 89.5′” x 54″

The standout, however, is the satin metallic silver hand sewn quilt titled Comforter. The quilt features the ominous, unfinished pyramid and all-seeing Eye of Providence motif of the Great Seal of the United States, found on the back of the one dollar bill. Sitting and sewing a quilt is the antithesis of the act of taking a snapshot. This slow process is more analogous to old chemical photo processing techniques, which required hours of patience before seeing the results. Unlike digital photography, hand developing photos is also becoming extinct like the daguerreotype, and the Bay Bridge—and the act of sewing could also become a fading art. Certainly, many hand-made things have gone the way of mass production. Yet, instant replication has been one of photography’s benefits since its invention and onset in the general market in the late 1800s, which brings up issues of originality. Comforter, on the contrary, evades the problem of originality that photography began to create for the art world. Additionally, its subject matter seems to epitomize everything that is wrong with the world: that almighty (questionably so) dollar. The quilt, along with the rest of the exhibition is deeply seated in rich and multiple interpretations of commodification, iconography, debt, wealth, nostalgia and so much more. Shaw puts these conversations of worth before us, reminding us that art has more to say than a dollar, which is a very potent comfort.

Gallery 16 @ Seattle Art Fair // Thursday, July 30 - August 2

July 28, 2015

Preview the work in our Seattle Art Fair page on Artsy.

PATRON VIP PASS - early access on July 30, 6-10 pm

TICKETS - single and three-day access

DATES, HOURS & LOCATION

SEATTLEARTFAIR.COM

Alice Shaw: Golden State // Opening July 17th 6-9pm

July 15, 2015

July 17 - September 4, 2015

Opening reception on Friday July 17 from 6 – 9pm

Gallery 16 is proud to present its fifth show with artist Alice Shaw, Golden State.

As the name suggests, Golden State, takes a look at the things that are important to the modern day culture in the California: religion, money, fame, booze, driving, and

parking.

Shaw is a photography based conceptual artist who frequently employs other media in her practice. For this exhibition she has included the ready made, collage, found imagery, fiber arts, and paint on canvas. Shaw grew up in California where people have been coming to find riches since before it was established in 1850. She lives and works in San Francisco.

Shaw’s art, which infuses personal document with humor, is included in the collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the di Rosa Foundation. She has practiced photography for over 20 years and she has been a visiting lecturer at UC Davis, UC Santa Cruz, UC Berkeley, San Francisco State University, CCA and The San Francisco Art Institute.

GALLERY 16 & UDC CLOSED JULY 3 - 5th

July 02, 2015

We will be closed Friday July 3rd & Saturday July 4th in observance of Independence Day. Apologies for any inconveniences. Have a great weekend, everyone!

Art Practical reviews Shaun O'Dell "Doubled"

June 23, 2015

http://www.artpractical.com/review/doubled/

By Leora Lutz

June 23, 2015

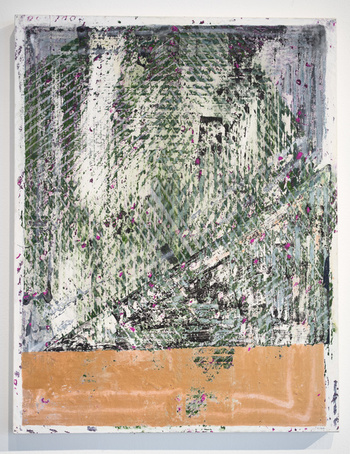

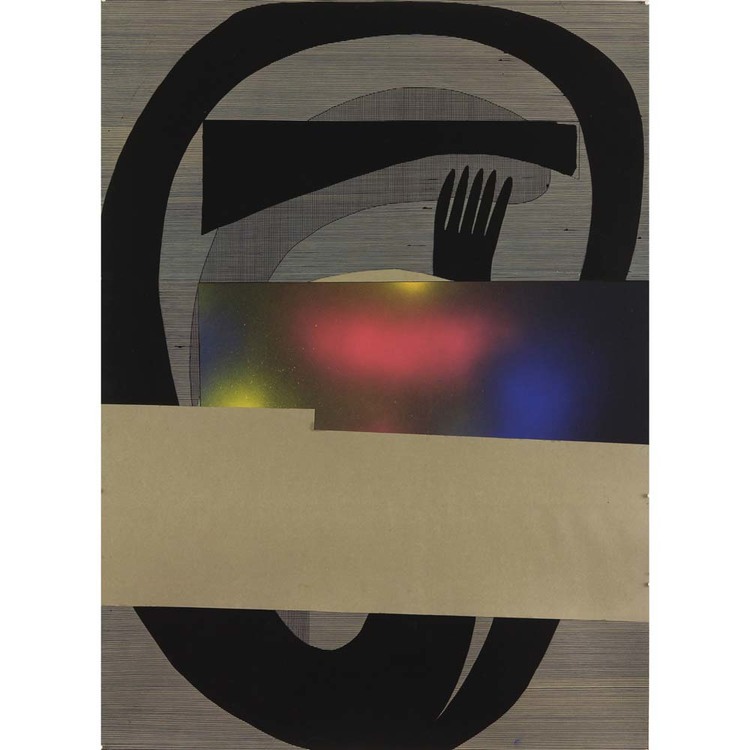

Shaun O’Dell’s second solo exhibition at Gallery 16 seems to be an incongruous flurry of the artist’s thoughts that carry over from daily life and find their way into the studio—however, first impressions can be deceiving. As the title Doubled implies, repetition abounds: films of owls, plants in pots, large murals, a suite of sculpture, airbrushed works on paper, pairs of drawings and photo transfers on marble, a series of paintings. A complex and poetically disjointed prose essay written by O’Dell supplements the exhibition, blending personal historical references with pop culture. The fragmented personal stories in the essay create threads of information that link the pieces. O’Dell confesses in the text: “I frequently experience slippages in my perception of time and lose track of where I am in the temporal landscape. My memory feels like it was erased or severely fragmented and I have a disorienting feeling that my memories are not my own.” He passes this deduction on to the viewer through doubling (not to be confused with mirroring or replicating), which political scholar Deems D. Morrione describes as “not merely destructive; it is also creative, as it produces a remainder”1 in his essay “When Signifiers Collide: Doubling, Semiotic Black Holes, and the Destructive Remainder of the American Un/Real.” Morrione opens the essay with an analysis of the Twin Towers as emblematic not only of architectural doubling, but also of the remaining space left behind as a result of their absence. So too can greater meaning be found in the remainders that O’Dell leaves for the viewer—the in-between space of his work, where no verbal or visual language resides.

One frequent departure point for O’Dell is the film Vertigo (1958), directed by Alfred Hitchcock. The film’s fixation with time sends O’Dell’s mind reeling with reminders of his family’s past, including a trip with his son to visit the Portals of the Past in Golden Gate Park, which is referenced in Vertigo. The structure of the portal is a marble replica of a classical Greek portico that was relocated to the park as a memorial to the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire; it stands now in front of lush forest trees at the end of Lloyd’s Lake—its double reflected in the water. Returning to Marrione, “The real and its stand-in are perceived to have equivalence.”2 Here, the portico’s new location is a somber reminder in a bucolic utopia. O’Dell counteracts the notion of utopia in portal.2.past.carls, (2015), which features a photograph of the portico on the lower portion of a black-and-white print with an image of the Carlsbad Caverns superimposed above, creating heaviness where treetops and sky once were. A conceptual double of the Carlsbad Caverns with an implied reference to Plato’s cave is seen in plato.dbl.SUNS.marble (2015), a black-and-white photo transfer of Plato’s concealed face on white marble. Further doubling occurs with the marble slab substrate acting as a double of the portico, while an image of two suns covering Plato’s face doubles as his eyes.

The sun thread continues in another part of the gallery, where two large murals on two different walls face each other across the span of the room. Titled The Dust (2015) and contributed by Emily Prince, one mural features a large sun demarcated by a black background drawn in charcoal, the dust from the drawing still present on the floor. Its exact inverse is across the way and can only be read as the moon, also hovering above fallen dust. The piece conjures existentialism and mortality awareness; its temporary home in the gallery will be gone when the show closes. Adjacent is an installation of various off-white abstract papier-mâché sculptures on small shelves attached to a black wall. The relics create a cabinet of curiosities, and the material replicates tan recyclable packing materials, similar to egg cartons. The question of use-value comes to mind here, and again in another untitled piece with completely blackened pages that is “modeled” after the Oxford Encyclopedia of Greek History. It is as if history or perhaps even books are dead. If that is the case, where is one to house encyclopedic knowledge ... or furthermore, if documentation is gone, how is anyone supposed to remember anything without some kind of visual reference, be it text or objects?

O’Dell’s recent area of conceptual focus draws from the book The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance by Franco “Bifo” Berardi. Berardi’s treatise on economy focuses on the dichotomous issues of growth and debt, wherein the two are forms of societal control enacted by the financial sector—particularly when agents of commerce attempt to influence the market by manipulating language. With that, Berardi proposes that poetry become a new form of political weaponry: “Poetry as the insolvency of language, as the sensuous birth of meaning and desire, as that which cannot be reduced to information and exchanged like currency.”3 This insolvency, Berardi suggests, implies that language alone can be bankrupt, and that real power is in the weight of each word. In the case of O’Dell, each object is made not simply for its face value, but also for its psychological currency, the poetry of visual language.

Shaun O’Dell: Doubled is on view at Gallery 16, in San Francisco, through July 10, 2015.

"Shaun O'Dell: Doubled" editorial recommendation by DeWitt Cheng for VAS

June 19, 2015

Shaun O’DellGallery 16, San Francisco, California Recommendation by DeWitt Cheng

Continuing through July 10, 2015

Shaun O’Dell’s mixed-media paintings and other works in “Doubled” look completely au courant in terms of their formal constructions, but an ironic lyricism clings to them, which the artist’s statement (more on this later) helps to illuminate. A wall-mounted array of paper-mache oddments, their familiar gray, oatmeal-lumpy material painted white, suggests artifacts or implements from some unknown civilization. A trio of minutely detailed paintings of airbrushed dots and squiggles atop a digitally printed image that has been pixelated into incomprehensibility questions the possibility of complete knowledge, while transforming the collision of modes into an immersive, compelling visual experience.

An abstraction with jagged black forms at the margins surrounding a gold (and implicitly heavenly, timeless) center/background turns out to be a high-contrast view of architecture against a cloudless sky. Photographic images of ruined classical architecture and an obscured portrait bust are printed on marble slabs. A handmade book, “modeled after the Oxford Encyclopedia of Greek History,” is composed of black pages. Large charcoal wall drawings of a sphere (like the expanding universe), gray and flecked, faces from across the gallery its opposite, a white circle surrounded by gray background radiation. O’Dell collaborates with his wife, Emily Prince, on works entitled “Dust,” which contain traces of their respective making: powdered charcoal fallen to the floor below. This is just a small sample of the work on view, not all of which explores these issues. A number of very fine abstractions live in the eternal present.

Be sure to read O’Dell’s statement, which links past and present; Hitchcock’s film about obsession and memory, “Vertigo;" the "Portals of the Past" in Golden Gate Park, relics from the1906 earthquake and fire; occultism; Black Magic cameras; Chris Marker’s visionary film "La Jetée;" and O’Dell’s great-grandfather’s photograph of Charlie Chaplin, whom writer Christian Berardi sees as personifying “a gentle modernity ... where different viewpoints can meet, conflict, and then find progressive agreement,” i.e., a liberal synthesis of utopian ideals and social realities. (See Chaplin’s still stirring Everyman speech from his 1940 satire, "The Great Dictator") Berardi sees 1977, when Chaplin died, as the beginning of the end of the physical commons, the year of the Apple II and Johnny Rotten’s musical proclamation of the death of the future. Let’s hope that technological humanity proves Einstein wrong and grows up; stay tuned.

Via Visual Art Source

Shaun O’Dell’s mixed-media paintings and other works in “Doubled” look completely au courant in terms of their formal constructions, but an ironic lyricism clings to them, which the artist’s statement (more on this later) helps to illuminate. A wall-mounted array of paper-mache oddments, their familiar gray, oatmeal-lumpy material painted white, suggests artifacts or implements from some unknown civilization. A trio of minutely detailed paintings of airbrushed dots and squiggles atop a digitally printed image that has been pixelated into incomprehensibility questions the possibility of complete knowledge, while transforming the collision of modes into an immersive, compelling visual experience.

An abstraction with jagged black forms at the margins surrounding a gold (and implicitly heavenly, timeless) center/background turns out to be a high-contrast view of architecture against a cloudless sky. Photographic images of ruined classical architecture and an obscured portrait bust are printed on marble slabs. A handmade book, “modeled after the Oxford Encyclopedia of Greek History,” is composed of black pages. Large charcoal wall drawings of a sphere (like the expanding universe), gray and flecked, faces from across the gallery its opposite, a white circle surrounded by gray background radiation. O’Dell collaborates with his wife, Emily Prince, on works entitled “Dust,” which contain traces of their respective making: powdered charcoal fallen to the floor below. This is just a small sample of the work on view, not all of which explores these issues. A number of very fine abstractions live in the eternal present.

Be sure to read O’Dell’s statement, which links past and present; Hitchcock’s film about obsession and memory, “Vertigo;" the "Portals of the Past" in Golden Gate Park, relics from the1906 earthquake and fire; occultism; Black Magic cameras; Chris Marker’s visionary film "La Jetée;" and O’Dell’s great-grandfather’s photograph of Charlie Chaplin, whom writer Christian Berardi sees as personifying “a gentle modernity ... where different viewpoints can meet, conflict, and then find progressive agreement,” i.e., a liberal synthesis of utopian ideals and social realities. (See Chaplin’s still stirring Everyman speech from his 1940 satire, "The Great Dictator") Berardi sees 1977, when Chaplin died, as the beginning of the end of the physical commons, the year of the Apple II and Johnny Rotten’s musical proclamation of the death of the future. Let’s hope that technological humanity proves Einstein wrong and grows up; stay tuned.

Via Visual Art Source

Shaun O'Dell, "Doubled" Reviewed by Sarah Hotchkiss on KQED

June 11, 2015

Shaun O’Dell Proffers Pairs and Portals at Gallery 16 by Sarah Hotchkiss for KQED

In his second solo exhibition at Gallery 16, Shaun O’Dell draws a meandering line through the past to the present, using layers, doubling and mimicry to tie together a disparate group of two-dimensional, sculptural and video works. O’Dell’s sprawling source material includes the 1906 earthquake and fire, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, pixelated images of technology components, an ancestor’s portrait of Charlie Chaplin and grainy footage of a Stanford robotics experiment.

Through recurring motifs and an accompanying exhibition statement, O’Dell gathers these bits and pieces into an exhibition that enacts a type of thinking that is complicated, cyclical and iterative. This methodology rejects the linear and orderly approach, and in doing so, trades predictability for true surprise.

Over and over in Doubled, things are — as expected — doubled. A video shows quick cuts of two owls puffing their feathers to face unseen foes. The Dust, two wall drawings by Emily Prince, grace O’Dell’s solo show with perfect wall-high circles of charcoal — one filled solid, the other inverted — on opposite sides of the room. And the aforementioned Chaplin portrait captures the star in a slightly shifted double exposure, his two eyes now four.

Even in the personal essay that doubles as an exhibition statement, O’Dell and Prince’s family histories are positioned as parallel narratives, two story lines that ultimately converge into one family unit.

Shrouding the exhibition in a layer of mysticism is a printed image on newsprint hanging behind the gallery’s desk.Portals.2.past.carls is split in two, the top half a photograph of Carlsbad Caverns, the lower half a view of Portals of the Past, a stone portico perched on the edge of Lloyd Lake in Golden Gate Park. Today this isolated bit of architecture functions as a memorial to those who lost their lives in 1906. Local legend holds the portico is a literal portal to the spirit world; ghostly sightings abound.

Portals of the Past figures in Hitchcock’s seminal psychological thriller Vertigo as a place where Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) falls into a trance. The doubling continues: In the film, “Madeleine” is actually the hired doppelgänger Judy Barton. And then there’s the portrait of Carlotta Valdes, another dead ringer for Madeleine/Judy/Kim.

In this way, fictional and real-life history intertwine throughoutDoubled until such classification becomes meaningless. In a real gesture of “rewriting” information, two large airbrush on paper pieces show O’Dell mimicking an underlying digital print (one an enlarged multicolored Intel chip, the other a zoomed-in view of Gallery 16 from above).

The “split” appears again and again in a series of nine same-sized paintings lining one wall of the exhibition. 9. PAINTINGappears to be a continuous work on paper cut in half, with one side flipped upside down and repositioned. This and other off-kilter gestures — like the positioning of a tiny video monitor behind a forest of potted plants — make exploring Doubled a bit like spelunking in a cave of the unexpected.

If, according to the exhibition text, we are to come to “the realization that the present and the past are simultaneous,” where does that leave the future? Doubled advocates for a view of time that retains such complications, allows space for meandering, unmediated experience and unabashedly mines the past for a more meaningful understanding of the present.

Essay by Shaun O'Dell

May 29, 2015

In conjunction with his current exhibition, Doubled, on view from May 21 - July 10 at Gallery 16.

//

Emily and I see Vertigo once a year when it plays at the Castro Theatre. There’s a reference in the film to The Portals of the Past - an old portico that sits on the shores of Lloyd Lake in Golden Gate Park. The portico served as the entryway to the Alban Towne mansion that burned down in the fire that engulfed the city after the 1906 earthquake. All that remained of the house after the fire was the portico. Arnold Genthe photographed it in full moonlight with the smoldering city framed between its blackened columns. It looks like the ruin of a Greek temple somehow survived the bombing of Hiroshima. During the rebuilding period the entryway was moved to the north bank of the small lake as a memorial to those who died in the earthquake and named The Portals of the Past.

In Vertigo, Gavin Elster asks Scottie if he believes that, ”...someone out of the past, someone dead, can enter and take possession of a living being?” He says that recently a cloud has come into his wife Madeline’s eyes and then they go blank and she wanders. He follows her one-day to Golden Gate Park where she sits on a bench and stares across the lake, “...at the pillars on the far shore, the Portals of the Past.”

Emily’s great-grandmother lived in the same apartment building as Madeline during the shooting of Vertigo. It’s called the Brockelbank at 1000 Mason just down the block from where the Towne mansion burned at 1101 California. Next door to the Brockelbank is the Fairmont Hotel at 950 Mason where my great-great grandfather was a chef. He lived a few blocks down the north side of Nob Hill on Jackson St with his wife and daughter, Mabel. When I was a kid, Mabel, my great-grandmother, would tell me about the earthquake. She said fire shot out of the street and burned up most of Nob Hill and that they lived for many weeks in a tent in Duboce Park half a block from where I now live.

A folk-story developed between the years the memorial was placed in the park and the making of Vertigo. The Portals of the Past gained attention in the international occult community as a seriously charged and active passageway between this world and other dimensions of time and space. There are stories about small luminous globes hovering over the lake and ghostly figures creeping around the columns. Spiritualists of the last century warned the inexperienced not to visit the site carelessly.

I took Leon on a bike ride to The Portals of the Past. We rode along the lake on a thin dirt path up to the bright marble steps. When we arrived there was a man with a tripod and a very sleek black video camera. He was filming something inside the portico at the top of one of the columns. Swallows were swooping all around us and frantic chirping filled the air. The man said he was filming the swallow chicks. He walked over to us and played back his recording of the mother hovering at the nest as the chicks ate from her beak. The HD resolution of the camera made the feeding scene horrific to me. The sharpness and detail of all the regurgitated stuff — craning baby bird necks with gaping beaks chirping wildly — crammed onto the tiny screen while the actual thing was happening just above our heads gave me an uneasy feeling. My anxiety intensified when he started talking about “black magic” and “the black magic people” interspersed with animated description of the cameras technical features.

I was beginning to turn the bike to leave when a man in a motorized wheelchair pulled up next to us. He turned the chair to face the lake and like Madeline stared quietly out over the water. The cameraman continued praising the Black Magic - which I now realized was the name of the camera manufacturer. Leon signaled that it was time to go and we pedaled off toward the beach.

“It does not seem to me, Austerlitz added, that we understand the laws governing the return of the past, but I feel more and more as if time did not exist at all, only various spaces interlocking according to the rules of a higher form of stereometry, between which the living and the dead can move back and forth as they like, and the longer I think about it the more it seems to me that we who are still alive are unreal in the eyes of the dead, that only occasionally, in certain lights and atmospheric conditions, do we appear in their field of vision. As far back as I can remember, said Austerlitz, I have always felt as if I had no place in reality, as if I were not there at all...”

-WG Sebald, Austerlitz, 2001

Chris Marker talks about seeing Vertigo when it was first released in 1958. He says that he stayed in the theatre for the rest of that day’s showings and returned the next day and the next until he had watched the film nineteen times. He goes on to say that the film produces a time portal on screen. Marker has said his film La Jetée – a film in which a man travels in time after nuclear apocalypse has destroyed most of the planet to ask the past and the future to rescue the present – is a direct response to Vertigo.

I am always shaken by the tragic intensity of the final scene in Vertigo. Scottie stares into the abyss knowing his obsessive act to remake the past has cast him into psychic oblivion - or in Marker’s words, a ”Vertigo of time.”

The Vertigo of time appears in La Jetée when after fifty days of trying to penetrate and remain in the past the Man succeeds and finds the Woman inside the Paris Museum of Natural History walking among taxidermied animals and large vitrines filled with stuffed birds. The animals and the Woman are timeless and perfect - they are ideal beings. This is a moment of ineffable emotional intensity. The Man is falling in love not only with the Woman, but also the time and the place of this love – the past. He has managed the same feat as Scotty and gone back in time to an idealized moment. The scene is saturated in heartbreak and longing. The Man has returned to the time and place that he knows has already been obliterated by the tragic decisions of the future. The Man also knows that the Woman is already dead. He can only be with her if he impossibly remains in the past. It is like Sandor Krasna in Marker’s film San Soleil says of Vertigo, “It is the only film capable of portraying impossible memory, insane memory.”

In the 1920s my great-grandfather Otto Schellenberg worked as a portrait photographer at Paramount and Universal Studios. There’s a family story that he took a portrait of Charlie Chaplin that my mother now has. I recently found a number of glass plate negatives credited to his studio in the collection of the Museum Of Man in San Diego. All the images are documentation of the opening exhibition of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition called, The Story of Man Through The Ages. The archive notes describe the photographs as “indoor portraits.” They are crisp large format images of naturally lit Arts and Crafts style exhibit halls filled with vitrines. The vitrines are packed with bronze and plaster busts showing age cycle and racial variation throughout man’s evolution as well as diorama’s of southwest Indians and their pottery, clothing, jewelry, drawings, and a collection of Peruvian skulls.

Otto’s photographs made me think of the museum scene in La Jetée with its vitrines and natural light cascading down from the skylights onto the faces of the Man and Woman and stuffed animals. In La Jetée, the Woman calls the Man her ”ghost” and here in Otto’s images, emptied of living people, I imagine them both as ghosts slipping and sliding between reflections in the cabinet glass. The title of the exhibition kept running through my mind, The Story of Man Through The Ages.

I frequently experience slippages in my perception of time and lose track of where I am in the temporal landscape. My memory feels like it was erased or severely fragmented and I have a disorienting feeling that my memories are not my own. A sense of loss and melancholy comes over me and it’s difficult to believe I ever existed or will exist in the future. I feel adrift in a changeless fog like time and memory have crystalized into an opaque nothingness.

Franco Berardi says the future is over. Time he says will go on, but our collective and personal belief in a better future has collapsed. The modernist dream of unending and more prosperous futures, are in ruins. The possibility to imagine a future is directly related to our material conditions. Our final utopian vision, technology and what Berardi calls the Wired ideology, were supposed to have made the world a better place with more equality, less working hours and more leisure. Instead we have a society in paralysis with occasional outbursts of rage.

In The Uprising, Berardi singles out the year 1977 as the point where the future begins to end. The Apple II is released and creates a “user friendly interface for the digital acceleration and unification of time.” It is also the year Johnny Rotten sings there is no future and that Charlie Chaplin dies. Berardi writes,

“...The death of that man, in my perception, represents the end of the possibility of a gentle modernity, the end of the perception of time as a contradictory, controversial place where different viewpoints can meet, conflict, and then find progressive agreement...Charlie Chaplin is the man on the watchtower, looking at the city from a perilous vantage point, looking at the city of time, but also at the city where time can be negotiated and governed...”

The sun and the moon at this moment in Earth’s history – even though the sun’s diameter is about 400 times larger than the moon – appear to be the same size because the sun is also 400 times farther away. So the sun and the moon appear nearly the same size as seen from Earth. This is why we can sometimes see a total eclipse of the sun. But as time passes the moon is slowly moving away from us. So, in the future it will be too small to cover the sun and we will no longer see a total eclipse from Earth.

Linear and cyclical time exist together in the universe. For almost all of Vertigo Scottie is caught in an eternal return: time is repeating for him. But at the climax of the movie the loop is severed by his obsession to make it everlasting. The tragedy hits him when the spiral unravels and time becomes linear again. The time of total eclipses on Earth is not fixed. Just as Scottie is eventually torn from his recursive fixation, so too will the perfectly doubled circles of sun and moon forever part. Eternity and impermanence coexist. The Vertigo of time is the realization that the present and the past are simultaneous.

- Shaun O’Dell, 2015

Shaun O'Dell: Doubled // Opening May 21 6-9 pm

May 07, 2015

We are excited to welcome back artist Shaun O’Dell for his second solo exhibition at

Gallery 16, on view May 21st to July 10th. Opening reception will be held Thursday,

May 21st from 6pm-9pm.

Doubled will be an exhibition of recent mixed media paintings, sculpture, video and

a pair of wall drawings by Emily Prince.

In Doubled, O’Dell started with an old portico in Golden Gate Park called The Portals

of the Past. His interest in the site comes from its reference in Hitchcock’s Vertigo

and his own experience of it on daily bike rides. In both the film and San Francisco

folklore the Portals of the Past are associated with the supernatural and a disruption

in our understanding of the physical world. O’Dell uses the Portals as a catalyst to

make an associative journey through autobiographical, historical and fictional

narratives that contribute to an impossible mapping of his position in space and time.

Recently, O’Dell has been influenced by Franco Berardi’s book, "The Uprising: On

Poetry and Finance". In the book Berardi describes the conjunctive and the

connective modes of thinking. The conjunctive is an associative kind of thinking. The

connective is a reduction of everything to straight lines and points (digitization comes

to mind) everything becomes standardized. O’Dell’s recent work is a reaction to

connective thinking becoming the dominant way in which society operates.

Shaun O'Dell was born in 1968 in Beeville, Texas. He is a graduate of Stanford

University’s MFA Program and has exhibited both nationally and internationally

appearing recently at Susan Inglett Gallery, New York; Inman Gallery, Houston; Jack

Hanley, New York; dOCUMENTA(13), Kassel; The A Foundation, Liverpool; Berkley

Art Museum, Berkley; CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, San Francisco and

San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco. His work can be found in the collections of

the Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney

Museum of American Art and the de Young Museum.

//